|

Eager Space | Videos by Alpha | Videos by Date | All Video Text | Support | Community | About |

|---|

https://www.nasa.gov/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/617036main_396093main_hsf_cmte_finalreport.pdf?emrc=e76114

In the past 20 years, two presidents tried to fix NASA human spaceflight. Neither of their plans really worked, but both led to situations that would require NASA to fundamentally change, both in the past and in the future.

It's a weird story.

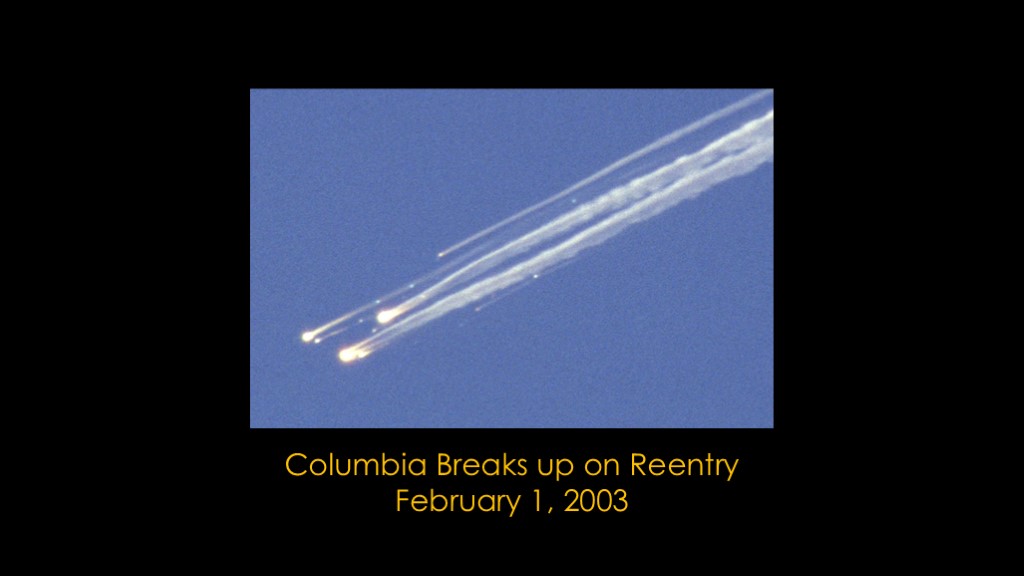

The story starts on February 1st, 2003, when the space shuttle Columbia broke up on reentry because of damage to the leading edge of the wing caused by foam that came off the external tank attachment to the shuttle.

The conventional view is that this was the reason that the shuttle program was cancelled, but that's not actually what happened.

Cancelling shuttle was never the plan. The plan was to bet on the status quo and keep flying shuttle for a long time.

And that's not surprising.

Everybody involved with shuttle at NASA, all the shuttle contractors spread across the country, and all the congresspeople in areas that have NASA centers or NASA contractors are used to the status quo, and many of the managers have built their careers around the shuttle program.

They would have to be idiots to want to give that up - the status quo approach is generally the low drama approach.

And I'm not picking on NASA; this is true for pretty much all successful big organizations.

And there was another big factor - Congress and NASA had decided to invest many billions of dollars to build the international space station and shuttle was the ticket to both finish the station and to carry both cargo and crew to the station.

I've come across a number of assertions that the Columbia Accident Report said that shuttle should be retired. Here's what the board actually said...

The board both believed that the shuttle was safe enough and could be recertified to fly into the 2020s.

Everything was aligned behind returning to flight and continuing to fly shuttle.

But not everybody...

The status was not quo.

NASA administrator Sean O'Keefe sensed that a big change in direction might be possible, but he would need support from the executive branch to figure out what that change should be and to implement it.

After discussion with the top people in the Bush administration, he convinced Stephen Hadley, deputy director of the highly influential National Security Council to work across agencies to figure out what the space plan would be going forward. That group eventually decided that going back to the moon was probably the best option.

President George W. Bush was signed up for the plan; he wanted to see if he could be successful where his father's space exploration initiative was not.

This new initiative was announced by president bush on January 14th, 2004.

It had 4 major goals:

The first was to return the shuttle to flight as soon as possible to complete the international space station, and then retire it. This seems like a strange approach, but the new space initiative required money and it was not possible from a budgetary perspective unless the very expensive shuttle program stopped.

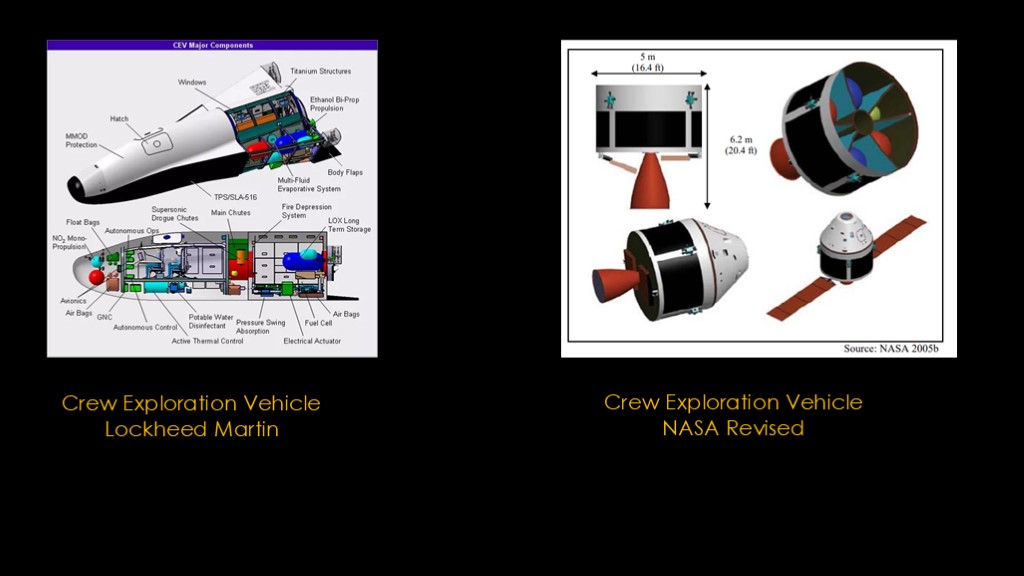

The second was to develop a new spacecraft, the crew exploration vehicle and conduct a crewed mission by 2014. That would leave a small gap between shuttle retiring and new missions to the ISS, but it wouldn't be terrible.

Return to the moon by 2020

And do human missions to Mars and beyond

This would turn out to be a watershed moment, a moment that changed that path of NASA forever. But I don't want to give away the ending...

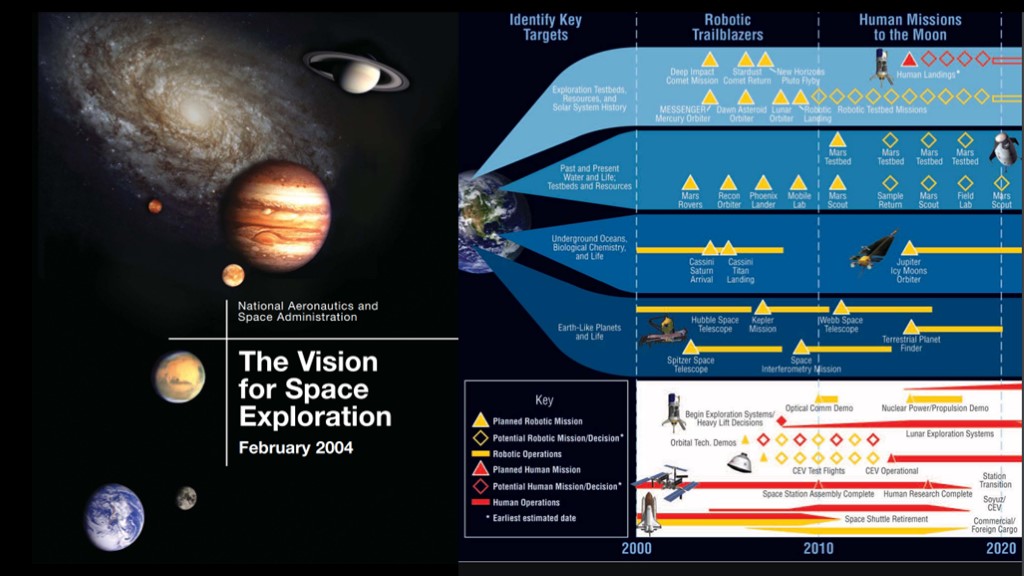

NASA responded soon after with their fleshing out of the plan, called The Vision for Space Exploration, which is pretty much everything that NASA had been talking about in exploration for the past couple decades...

There were two big problems...

The first is that the program NASA outlined was very ambitious and it would be very hard to accomplish under any budget NASA could expect.

The second problem was that the vision did not align with all the people who were happy with the shuttle status quo.

The status quo group bought a lucky break when Administrator O'Keefe decided to leave his position in early 2005. His official reason was that becoming Chancellor of Louisiana State University would pay better and allow him to better support his family, but it was clear that he was very tired from Columbia and the strain of trying to reform NASA.

He was replaced by Michael Griffin, who was much more in line with the traditional NASA approach. He was comfortable with the approach building new rockets from shuttle parts and argued that it would be quicker than starting from scratch. That was key to the approach outlined in NASA's exploration systems architecture study

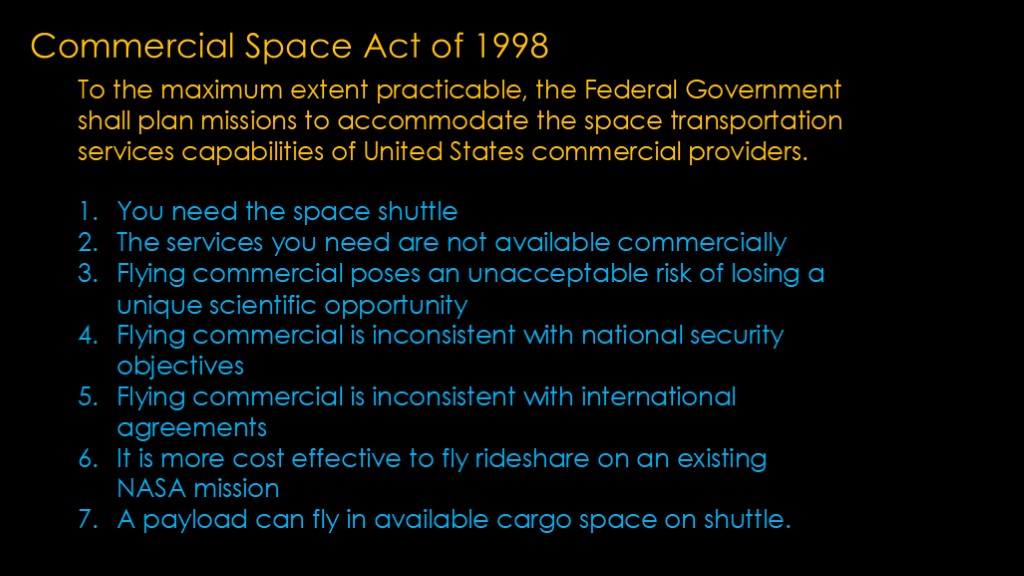

But Griffin had a problem, and that problem was the commercial space act.

The commercial space act says the following:

(read)

There are 7 exceptions, and you need to fly commercial unless you can hit one of those exceptions.

Griffin decided to lean heavily on exception #2. Obviously big missions like going to the moon were things that only NASA could do.

To meet that exception the mission had to be modified.

The crew exploration contract was modified in process to change from a "bring what you want" design that could fly on commercial launchers to a "big capsule with a service module" design.

Orion was just big enough that it was too heavy to fly Atlas V or Delta IV, and any way, those launchers would need new second stages and they use small solid rocket boosters that aren't safe, not like the big solid rocket boosters that NASA flies.

That may sound like it violates the spirit of the commercial space act, but it's only a violation if somebody complains.

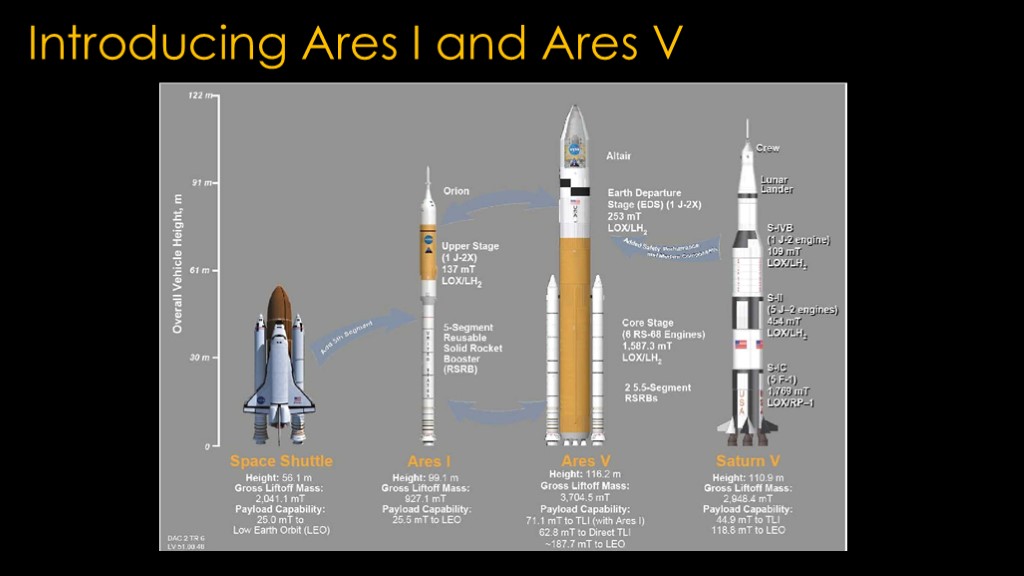

It was therefore decided that NASA would build two new rockets.

The new rockets are Ares I and Ares V, both mostly made out of shuttle parts, which was what Griffin had decided. That mostly made the status quo crowd happy; the NASA centers would be able to work on the same sort of projects and most of the manufacturers would still be making shuttle parts.

NASA had another need, and that was supplying the Space Station with cargo. It was hard to make an argument that commercial providers could not launch payloads into low earth orbit since pretty much every commercial rocket was designed to do exactly that, so we got

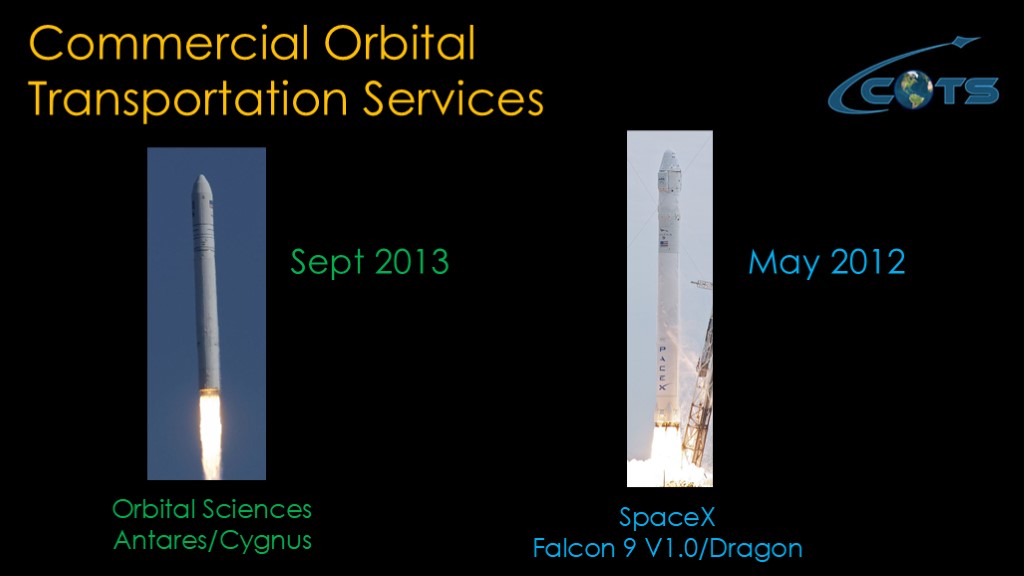

The commercial orbital transportation services program in 2006. This was the first time that NASA human spaceflight had agreed to buy a service from a commercial provider.

After a bit of drama, NASA settled on two providers. The first was a sure bet, with Orbital Sciences flying their Antares rocket and Cygnus resupply spacecraft. It took them 6 years and they were a couple years after the shuttle retired, but Congress slow-rolled the initial funding to slow things down.

Yes, it is strange that congress underfunds a program directly authorized by congress and in line with a space act that congress had also passed, but it's important to remember that legislation and funding are two separate things run by different people.

The status quo folks liked Orbital Sciences because they had a proven track record and had a goal of selling their services to the government and making a nice profit and nothing beyond that.

The second award went to an upstart company know as Space Exploration Technologies who had just flown their first rocket to orbit. They built a medium launch lifter plus a cargo capsule named dragon to go with it and their first flight to ISS was in May of 2012, about 16 months earlier than Orbital Sciences.

This made NASA happy - they still relied on the Russians to carry astronauts to ISS but at least they could get cargo.

And the Ares I rocket would soon be ready to fly astronauts.

Time to look back again.

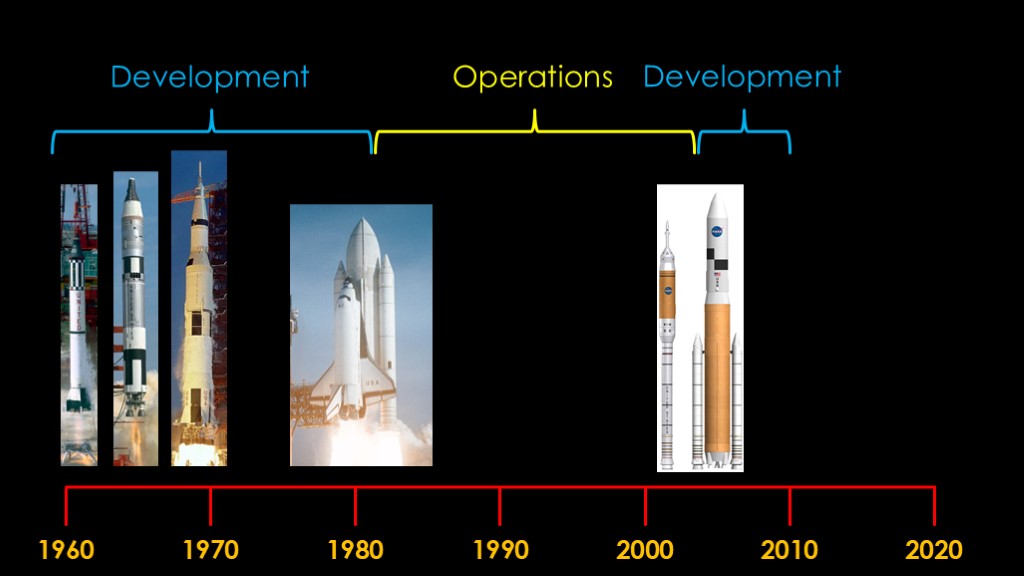

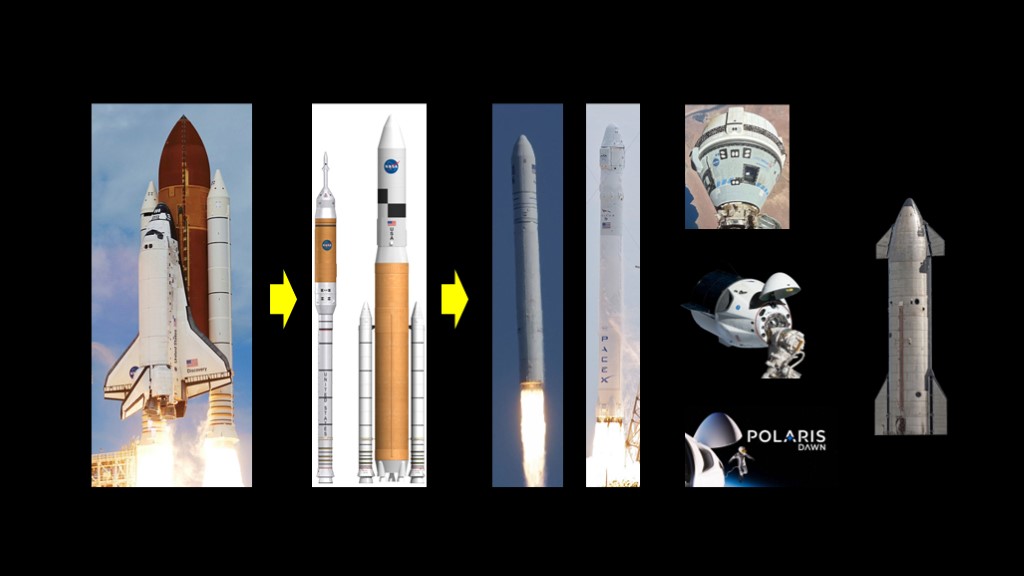

NASA Spaceflight launched the first US astronaut into space in 1961 in project Mercury, and followed with Gemini in 1965, and finally, Apollo 11 reached the moon in 1969. Three unique systems in 10 years, though Mercury and Gemini did fly on existing missiles.

In 1974, NASA started working on the space shuttle, and in 1981 it finally took flight. During the 20 years from 1961 to 1981, NASA was a development organization; designing new things and figuring out how to make them work. That took a special kind of organizational culture and a special kind of management to make it work.

In 1981, NASA stopped doing development; their goal now was to just fly shuttle over and over with minimal modifications. That creates a different kind of organization and NASA was run by managers instead of by engineers; many of the Apollo and Shuttle engineers left or retired.

That shift was certainly a factor in the loss of both Challenger and Columbia, but that's not the issue I want to talk about here. The problem at hand is that NASA spaceflight has signed up to do development work on this huge new project that is arguably harder than Apollo in architecture, and it's been 30 years since they developed shuttle.

NASA started executing on Constellation.

During this time, congress was getting a little concerned about depending on Russia for both cargo - commercial cargo hadn't flow yet - and crew access to the international space station.

The 2008 NASA authorization act directed NASA to use commercial provided crew services to the space station as much as possible and limit the use of the crew exploration vehicle - soon to be named Orion - to missions beyond low earth orbit.

That seems like a pretty clear directive, but remember that authorizations tell NASA that it can do something but don't actually provide money to do it.

The appropriations act included this, which basically says that if NASA has any leftover money from the COTs cargo program they should spend it on commercial crew. Not exactly a ringing endorsement of the concept, and NASA is still officially the organization that flies humans in the US.

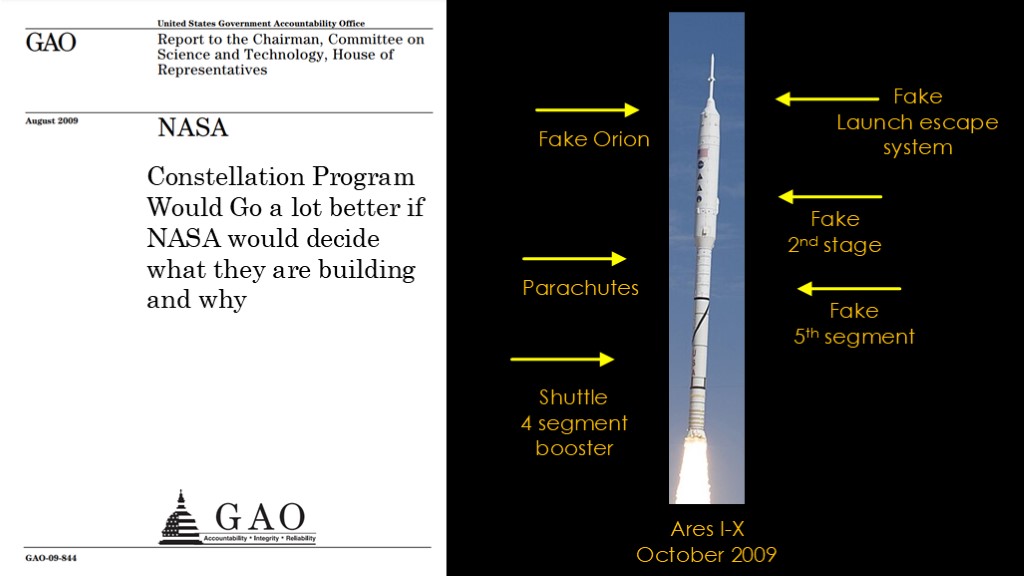

As is common with large NASA programs that spend a lot of money, the government accountability office had been watching the Constellation Program, and in August of 2009, they issued this report, entitled:

Constellation program would go a lot better if NASA would decide what they are building and why.

That's a bit of a paraphrase; the actual title is "constellation program cost and schedule will remain uncertain until a sound business case is established".

In October 2009, the Ares I-X was launched to gather performance data on the first stage solid rocket booster.

It flew a standard shuttle 4 segment solid rocket booster, with a fake 5th segment on top and then parachutes for recovery. On top of that was a fake second stage, a fake orion, and a fake launch escape system. The fake sections were instrumented to gather data about the test.

The test was successful, with the booster performing great, separating, and then parachuting back into the sea.

Presumably this test was intended to show the progress NASA had made, but what it amply demonstrated is that NASA had no new hardware ready to fly for Ares I with the exception of the larger parachutes designed for the 5 segment booster.

What did we learn from constellation?

The first is that NASA doesn't know how to run a development program any more. This really wasn't that much of a surprise; President Bush had put together a commission in 2004 and one of their conclusions was (read).

The second is that NASA had no solution for ISS crew and cargo. It was 2010, shuttle was going to retire very soon, and NASA was not on a path to flying a replacement. The only solution was to fly astronauts and cargo on Russian rockets and that makes NASA look very stupid.

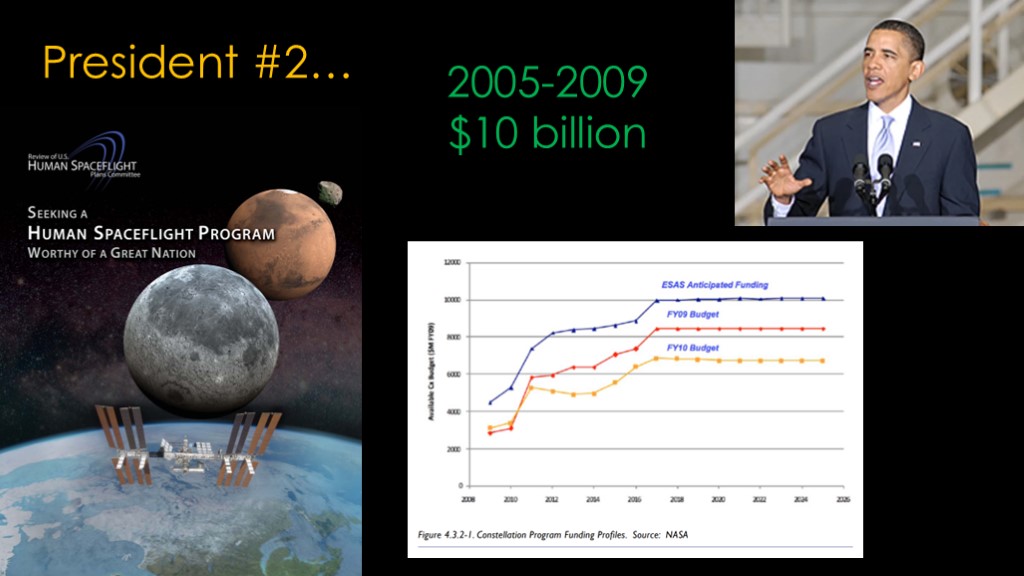

In 2009, President Obama took office and immediately commissioned a review of the current space program, and that committee released their report in October of 2009. This is one of the best reviews I've seen done and is still worth a read now; there's a link in the video description.

This graph is eye opening. The projected budget for constellation was $10 billion a year. The FY10 budget would likely set that level to $7 billion a year, and this chart does not include the cost for the ground systems - launch pads etc. - which would move to constellation when shuttle retired. That meant that Constellation was $3-4 billion short per year even if it met the NASA estimates, which it was already exceeding.

The report listed a number of different options on how to proceed, noted that constellation had already spent $10 billion over 5 years and only produced one test launch. Obama looked at the different options and decided to cancel constellation in 2010, excluding it from the proposed budget request.

https://www.nasa.gov/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/617036main_396093main_hsf_cmte_finalreport.pdf?emrc=e76114

The reaction of the status quo was swift. Florida Senator Bill Nelson - yes, the same Bill Nelson that current runs NASA - claimed that "the president made a mistake", playing the "you aren't the boss of me!" card. He was correct; it is Congress that has the power to decide what NASA does, and they have been happy to defund programs that the president chose and fund programs that the president did not choose.

Nelson went on to tell Obama that he will see him in the parking lot after school, or, to be more specific, at the President's Space summit on April 15th.

Like President Bush, Obama was hoping to transform how NASA worked, and he laid out his thoughts in a speech at the summit.

Not surprisingly, his first point was to cancel constellation because it was not fulfilling its promise in many ways.

His second point was to buy space transportation from commercial operations. The idea of flying astronauts on non-NASA vehicles really chafes with those who believe in NASA uniqueness, but it was really clear that NASA had no current plan to carry astronauts to ISS, which means that it was either commercial space or the Russians.

The next point was to skip the moon and go directly to Mars. Here I think Obama was really underinformed about the current state of NASA's capabilities; NASA couldn't execute on constellation to get to the moon and mars was oh so much harder.

Then the two big ones - develop orion into a crew rescue vehicle for ISS, and spend $3 billion to research a new heavy lift rocket, focusing on new designs, new materials, and new technologies.

The status quo looked at this and said, "I think we can work with this"...

Obama's plan morphed in congress into the NASA authorization act of 2010.

Congress gave a big check mark to cancelling constellation, so there was no mention of constellation in the act.

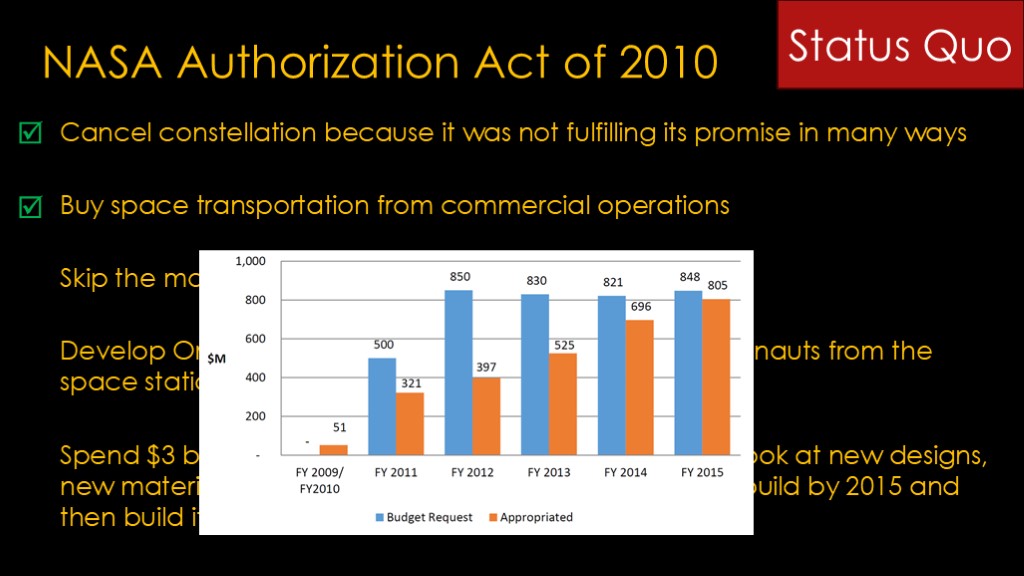

Buying commercial transportation also got a check mark, very grudgingly, and Congress decided to underfund it for the first 4 years. Congress apparently prefers a world in which the Russians fly astronauts over a world where US companies fly astronauts.

The moon or mars question got punted down the road. The act talks extensively about missions but typically refers to them as "missions beyond low earth orbit"

The Orion section got a check but only once it was rescoped to continue the Orion program from Constellation, with a requirement to be able to deliver crew and cargo to the ISS if necessary. Remember that congress hates commercial crew and cargo.

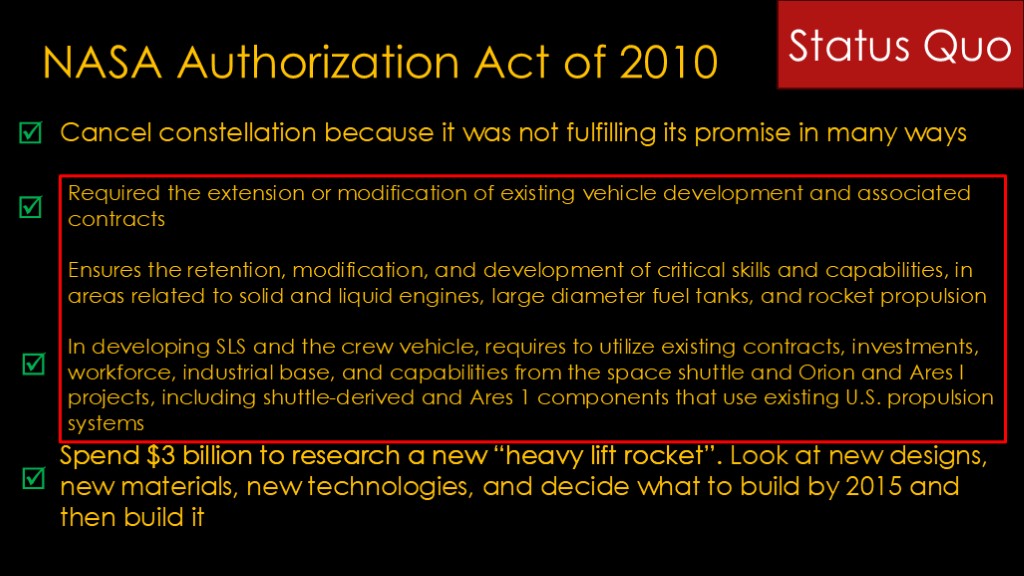

And finally, the status quo loved the idea of a new heavy lift rocket, which they would call the "space launch system", or SLS.

They didn't like all this talk about new designs, new materials and new technologies, so they got rid of all that.

To make it very clear, they spelled things out in detail.

The act required extending or modifying existing vehicle development contracts.

It required the retention, modification, and development on critical skills and capabilities that just happened to be those that were used by shuttle.

It had to use anything that was shuttle-derived or had been started on Ares I.

It was basically a very clear requirement that SLS had to be shuttle derived, which was exactly what had been going on with constellation. So the real change was to rebrand constellation as SLS/Orion and get rid of the Ares I option. The status quo made sure there was no chance NASA could make a different choice.

So, once again, a President had failed to redirect NASA. The status quo still reigned supreme...

But maybe not...

I have said in the past the George W. Bush was merely trying to create a legacy for himself, but the thoughtful way in which his administration worked with administrator O'Keefe has impressed me. They wanted a legacy, but they were also tired of astronauts being killed on flights carrying cargo into low earth orbit.

Their plan did not work the way they had hoped, and the status quo and Administrator Griffin gave us a shuttle-derived plan.

But their plan did uncover NASA's inability to build a new vehicle to service ISS, and that gave us the unicorn that is SpaceX.

Without their plan and the cancellation of shuttle, there's a decent chance that SpaceX does not survive.

The plan from the Obama administration also did not work as intended, but like the Bush plan, it set a couple things in motion.

With the decision to cancel Constellation is was very clear that NASA had no solution to carrying crew to ISS, and that meant either commercial crew had to go forward - in line with what congress required - or NASA had to keep sending large sum of money to Russia and accept a space station that was chronically undercrewed.

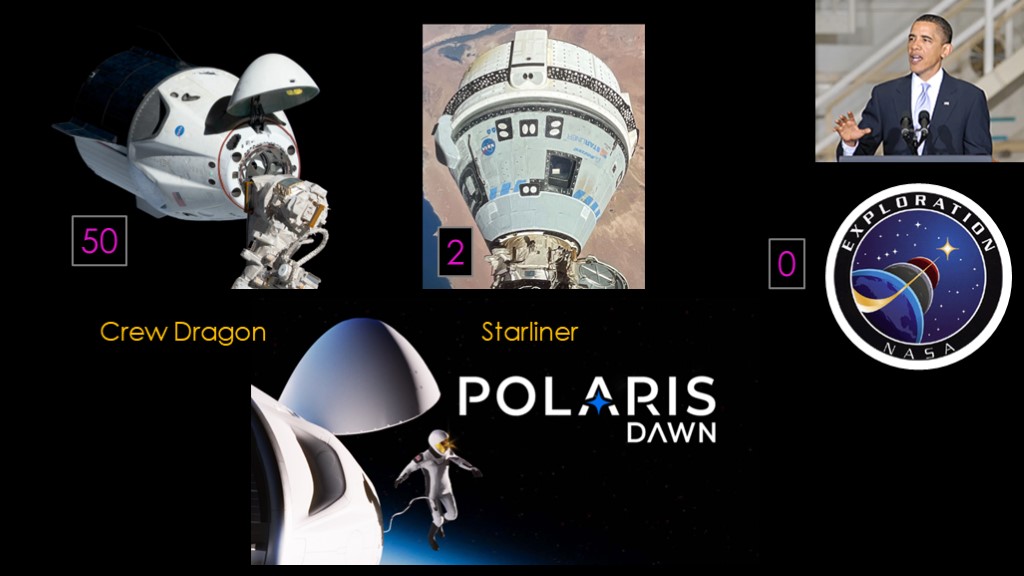

We therefore got SpaceX's crew Dragon, and Boeing's Starliner capsule.

Since shuttle retired, crew dragon has flown 50 humans into space, and starliner is in the middle of its first crewed flight, flying 2 astronauts.

Vehicles developed by NASA's exploration division have flown a total of zero humans during that time period.

NASA has not just lost their monopoly on launching humans from the US, they have lost their ability. That may come back with Artemis II, but in an area where NASA was the only game in town they are lagging far behind.

And this has also spawned the Polaris program, which is Jared Isaacman and SpaceX's very own Gemini program, bypassing NASA to develop those capabilities.

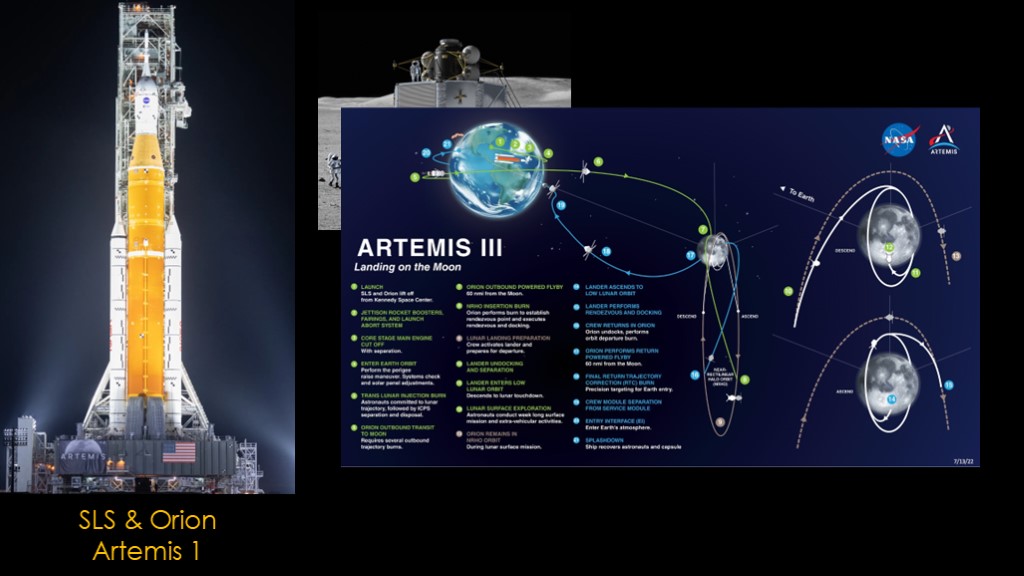

And, because SLS and Orion have never been part of a coherent moon architecture, the heavy lift rocket and capsule that they built could only get humans into lunar orbit.

The constellation project had a big lander known as Altair, but it didn't make it into to SLS & Orion world, so the Artemis moon story is a story without a NASA LANDER.

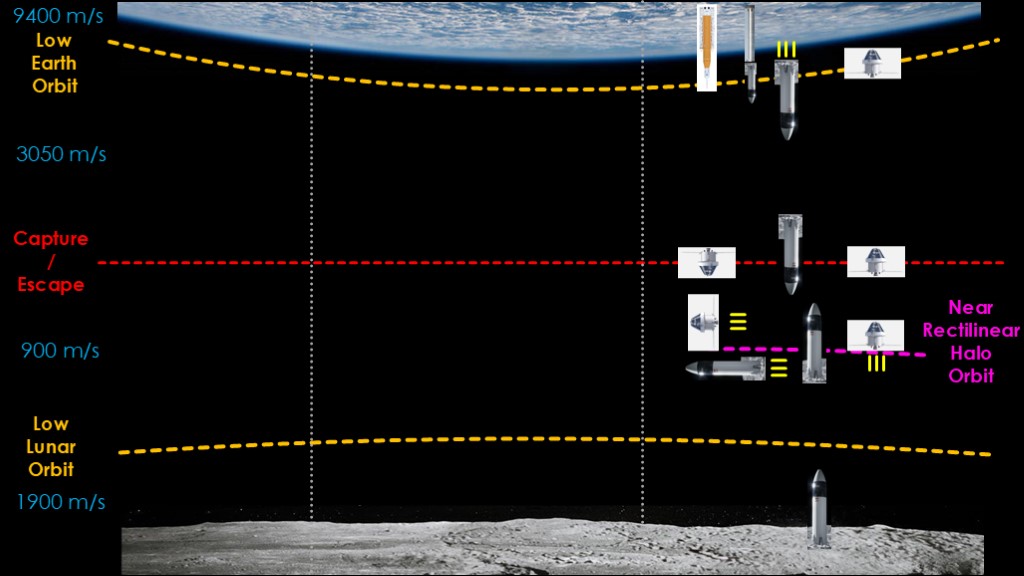

The huge SLS and Orion can get into an easy-to-get-to lunar orbit, known as Near Rectilinear Halo Orbit, and Orion can get back home, but all they provide is a sightseeing tour.

NASA needed a lander, but SLS couldn't carry one that was big enough.

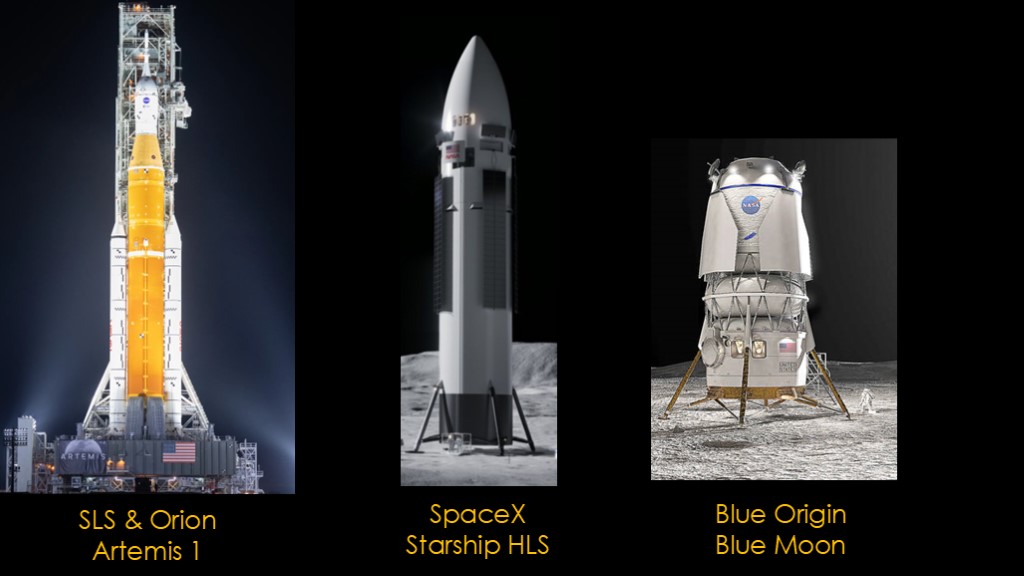

Stealing a slide from my video on the Artemis architecture - go watch that for the details -

We see that SLS launches Orion and Orion brakes into near a near rectilinear halo orbit.

A lander is launched into low earth orbit, refueled, and flies out and meets up with Orion. Astronauts transfer over, and the lander lands then. On the return trip, it goes back to orion, transfers the astronauts back, and Orion heads back for home, leaving the lander in lunar orbit.

NASA has contracted to get two different landers. SpaceX will build a version of Starship optimized for the lunar mission, and Blue Origin will build a lander known as blue moon.

What may not be clear is that is technically quite a bit harder to get a lander to the moon, land, and get back into orbit than merely to get a capsule in to orbit, so NASA is helping pay for two projects that are much more capable than SLS and Orion, and there are obvious ways that those architectures could be modified to do the entire moon mission without SLS and Orion. And with SLS & Orion costing on the order of $4 billion and only capable of flying once a year, it seems likely that the commercial moon architectures will be developed.

This happened because the status quo was more focused on the money and jobs side when they set of SLS and Orion and didn't consider that there might be commercial companies capable of outdoing what NASA could do.

And that's where we are.

Two presidents made attempts to reform and reimagine how NASA does things, and both of those attempts failed - they did not achieve what the presidents wanted to achieve.

But they both forced NASA - and more importantly, congress - to adapt, and those adaptations change the US spaceflight world in ways that pushed NASA into a world where NASA relies on commercial providers far more than anybody had thought possible, and that trend is only going to continue.

If you enjoyed this video, please buy yourself this book...